- Home

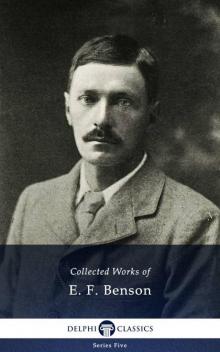

- E. F. Benson

Works of E F Benson Page 22

Works of E F Benson Read online

Page 22

At another of these informal seances attended by Goosie and Mrs Antrobus, even stranger things had happened, for the Princess’s hands, as they held a little preliminary conversation, began to tremble and twitch even more strongly than Colonel Boucher’s, and Mrs Quantock hastily supplied her with a pencil and a quantity of sheets of foolscap paper, for this trembling and twitching implied that Reschia, an ancient Egyptian priestess, was longing to use the Princess’s hand for automatic writing. After a few wild scrawls and plunges with the pencil, the Princess, though she still continued to talk to them, covered sheet after sheet in large flowing handwriting. This, when it was finished and the Princess sunk back in her chair, proved to be the most wonderful spiritual discourse, describing the happiness and harmony which pervaded the whole universe, and was only temporarily obscured by the mists of materiality. These mists were wholly withdrawn from the vision of those who had passed over. They lived in the midst of song and flowers and light and love…. Towards the end there was a less intelligible passage about fire from the clouds. It was rendered completely intelligible the very next day when there was a thunderstorm, surely an unusual occurrence in November. If that had not happened Mrs Quantock’s interpretation of it, as referring to Zeppelins, would have been found equally satisfactory. It was no wonder after that, that Mrs Antrobus, Piggy and Goosie spent long evenings with pencils and paper, for the Princess said that everybody had the gift of automatic writing, if they would only take pains and patience to develop it. Everybody had his own particular guide, and it was the very next day that Piggy obtained a script clearly signed Annabel Nicostratus and Jamifleg followed very soon after for her mother and sister, and so there was no jealousy.

But the crown and apex of these manifestations was undoubtedly the three regular seances which took place to the three select circles after dinner. Musical boxes resounded, violins gave forth ravishing airs, the sitters were touched by unseen fingers when everybody’s hands were touching all around the table, and from the middle of it materialisations swathed in muslin were built up. Pocky came, visible to the eye, and played spirit music. Amadeo, melancholy and impressive, recited Dante, and Cardinal Newman, not visible to the eye but audible to the ear, joined in the singing “Lead, Kindly Light,” which the secretary requested them to encourage him with, and blessed them profusely at the conclusion. Lady Ambermere was so much impressed, and so nervous of driving home alone, that she insisted on Georgie’s going back to the Hall with her, and consigning her person to Pug and Miss Lyall, and for the three days of the Princess’s visit, there was practically no subject discussed at the parliaments on the Green, except the latest manifestations. Olga went to town for a crystal, and Georgie for a planchette, and Riseholme temporarily became a spiritualistic republic, with the Princess as priestess and Mrs Quantock as President.

Lucia, all this time, was almost insane with pique and jealousy, for she sat in vain waiting for an invitation to come to a seance, and would, long before the three days were over, have welcomed with enthusiasm a place at one of the inferior and informal exhibitions. Since she could not procure the Princess for dinner, she asked Daisy to bring her to lunch or tea or at any hour day or night which was convenient. She made Peppino hang about opposite Daisy’s house, with orders to drop his stick, or let his hat blow off, if he saw even the secretary coming out of the gate, so as possibly to enter into conversation with him, while she positively forced herself one morning into Daisy’s hall, and cried “Margarita” in silvery tones. On this occasion Margarita came out of the drawing-room with a most determined expression on her face, and shut the door carefully behind her.

“Dearest Lucia,” she said, “how nice to see you! What is it?”

“I just popped in for a chat,” said she. “I haven’t set eyes on you since the evening of the Spanish quartette.”

“No! So long ago as that is it? Well, you must come in again sometime very soon, won’t you? The day after tomorrow I shall be much less busy. Promise to look in then.”

“You have a visitor with you, have you not?” asked Lucia desperately.

“Yes! Two, indeed, dear friends of mine. But I am afraid you would not like them. I know your opinion about anything connected with spiritualism, and — isn’t it silly of us? — we’ve been dabbling in that.”

“Oh, but how interesting,” said Lucia. “I — I am always ready to learn, and alter my opinions if I am wrong.”

Mrs Quantock did not move from in front of the drawing-room door.

“Yes?” she said. “Then we will have a great talk about it, when you come to see me the day after tomorrow. But I know I shall find you hard to convince.”

She kissed the tips of her fingers in a manner so hopelessly final that there was nothing to do but go away.

Then with poor generalship, Lucia altered her tactics, and went up to the Village Green where Piggy was telling Georgie about the script signed Annabel. This was repeated again for Lucia’s benefit.

“Wasn’t it too lovely?” said Piggy. “So Annabel’s my guide, and she writes a hand quite unlike mine.”

Lucia gave a little scream, and put her fingers to her ears.

“Gracious me!” she said. “What has come over Riseholme? Wherever I go I hear nothing but talk of seances, and spirits, and automatic writing. Such a pack of nonsense, my dear Piggy. I wonder at a sensible girl like you.”

Mrs Weston, propelled by the Colonel, whirled up in her bath-chair.

“‘The Palmist’s Manual’ is too wonderful,” she said, “and Jacob and I sat up over it till I don’t know what hour. There’s a break in his line of life, just at the right place, when he was so ill in Egypt, which is most remarkable, and when Tommy Luton brought round my bath-chair this morning — I had it at the garden-door, because the gravel’s just laid at my front-door, and the wheels sink so far into it— ‘Tommy,’ I said, ‘let me look at your hand a moment,’ and there on his line of fate, was the little cross that means bereavement. It came just right didn’t it, Jacob? when he was thirteen, for he’s fourteen this year, and Mrs Luton died just a year ago. Of course I didn’t tell Tommy that, for I only told him to wash his hands, but it was most curious. And has your planchette come yet, Mr Georgie? I shall be most anxious to know what it writes, so if you’ve got an evening free any night soon just come round for a bit of dinner, and we’ll make an evening of it, with table turning and planchette and palmistry. Now tell me all about the seance the first night. I wish I could have been present at a real seance, but of course Mrs Quantock can’t find room for everybody, and I’m sure it was most kind of her to let the Colonel and me come in yesterday afternoon. We were thrilled with it, and who knows but that the Princess didn’t write the Palmist’s Manual for on the title page it says it’s by P. and that might be Popoffski as easily as not, or perhaps Princess.”

This allusion to there not being room for everybody was agony to Lucia. She laughed in her most silvery manner.

“Or, perhaps Peppino,” she said. “I must ask mio caro if he wrote it. Or does it stand for Pillson? Georgino, are you the author of the Palmist’s Manual? Ecco! I believe it was you.”

This was not quite wise, for no one detested irony more than Mrs Weston, or was sharper to detect it. Lucia should never have been ironical just then, nor indeed have dropped into Italian.

“No” she said. “I’m sure it was neither Il Signer Peppino nor Il Signer Pillson who wrote it. I believe it was the Principessa. So, ecco! And did we not have a delicious evening at Miss Bracely’s the other night? Such lovely singing, and so interesting to learn that Signor Cortese made it all up. And those lovely words, for though I didn’t understand much of them, they sounded so exquisite. And fancy Miss Bracely talking Italian so beautifully when we none of us knew she talked it at all.”

Mrs Weston’s amiable face was crimson with suppressed emotion, of which these few words were only the most insignificant leakage, and a very awkward pause succeeded which was luckily broken by everybody beginn

ing to talk again very fast and brightly. Then Mrs Weston’s chair scudded away; Piggy skipped away to the stocks where Goosie was sitting with a large sheet of foolscap, in case her hand twitched for automatic script, and Lucia turned to Georgie, who alone was left.

“Poor Daisy!” she said. “I dropped in just now, and really I found her very odd and strange. What with her crazes for Christian Science, and Uric Acid and Gurus and Mediums, one wonders if she is quite sane. So sad! I should be dreadfully sorry if she had some mental collapse; that sort of thing is always so painful. But I know of a first-rate place for rest-cures; I think it would be wise if I just casually dropped the name of it to Mr Robert, in case. And this last craze seems so terribly infectious. Fancy Mrs Weston dabbling in palmistry! It is too comical, but I hope I did not hurt her feelings by suggesting that Peppino or you wrote the Manual. It is dangerous to make little jokes to poor Mrs Weston.”

Georgie quite agreed with that, but did not think it necessary to say in what sense he agreed with it. Every day now Lucia was pouring floods of light on a quite new side of her character, which had been undeveloped, like the print from some photographic plate lying in the dark so long as she was undisputed mistress of Riseholme. But, so it struck him now, since the advent of Olga, she had taken up a critical ironical standpoint, which previously she had reserved for Londoners. At every turn she had to criticise and condemn where once she would only have praised. So few months ago, there had been that marvellous Hightum garden party, when Olga had sung long after Lady Ambermere had gone away. That was her garden party; the splendour and success of it had been hers, and no one had been allowed to forget that until Olga came back again. But the moment that happened, and Olga began to sing on her own account (which after all, so Georgie thought, she had a perfect right to do), the whole aspect of affairs was changed. She romped, and Riseholme did not like romps; she sang in church, and that was theatrical; she gave a party with the Spanish quartette, and Brinton was publicly credited with the performance. Then had come Mrs Quantock and her Princess, and, lo, it would be kind to remember the name of an establishment for rest-cures, in the hope of saving poor Daisy’s sanity. Again Colonel Boucher and Mrs Weston were intending to get married, and consulted a Palmist’s Manual, so they too helped to develop as with acid the print that had lain so long in the dark.

“Poor thing!” said Lucia, “it is dreadful to have no sense of humour, and I’m sure I hope that Colonel Boucher will thoroughly understand that she has none before he speaks the fatal words. But then he has none either, and I have often noticed that two people without any sense of humour find each other most witty and amusing. A sense of humour, I expect, is not a very common gift; Miss Bracely has none at all, for I do not call romping humour. As for poor Daisy, what can rival her solemnity in sitting night after night round a table with someone who may or may not be a Russian princess — Russia of course is a very large place, and one does not know how many princesses there may be there — and thrilling over a pot of luminous paint and a false nose and calling it Amadeo the friend of Dante.”

This was too much for Georgie.

“But you asked Mrs Quantock and the Princess to dine with you,” he said, “and hoped there would be a seance afterwards. You wouldn’t have done that, if you thought it was only a false nose and a pot of luminous paint.”

“I may have been impulsive,” said Lucia speaking very rapidly. “I daresay I’m impulsive, and if my impulses lie in the direction of extending such poor hospitality as I can offer to my friends, and their friends, I am not ashamed of them. Far otherwise. But when I see and observe the awful effect of this so-called spiritualism on people whom I should have thought sensible and well-balanced — I do not include poor dear Daisy among them — then I am only thankful that my impulses did not happen to lead me into countenancing such piffle, as your sister so truly observed about POOR Daisy’s Guru.”

They had come opposite Georgie’s house, and suddenly his drawing-room window was thrown up. Olga’s head looked out.

“Don’t have a fit, Georgie, to find me here” she said. “Good morning, Mrs Lucas; you were behind the mulberry, and I didn’t see you. But something’s happened to my kitchen range, and I can’t have lunch at home. Do give me some. I’ve brought my crystal, and we’ll gaze and gaze. I can see nothing at present except my own nose and the window. Are you psychical, Mrs Lucas?”

This was the last straw; all Lucia’s grievances had been flocking together like swallows for their flight, and to crown all came this open annexation of Georgie. There was Olga, sitting in his window, all unasked, and demanding lunch, with her silly ridiculous crystal in her hand, wondering if Lucia was psychical.

Her silvery laugh was a little shrill. It started a full tone above its normal pitch.

“No, dear Miss Bracely,” she said. “I am afraid I am much too commonplace and matter-of-fact to care about such things. It is a great loss I know, and deprives me of the pleasant society of Russian princesses. But we are all made differently; that is very lucky. I must get home, Georgie.”

It certainly seemed very lucky that everyone was not precisely like Lucia at that moment, or there would have been quarrelling.

She walked quickly off, and Georgie entered his house. Lucia had really been remarkably rude, and, if allusion was made to it, he was ready to confess that she seemed a little worried. Friendship would allow that, and candour demanded it. But no allusion of any sort was made. There was a certain flush on Olga’s face, and she explained that she had been sitting over the fire.

The Princess’s visit came to an end next day, and all the world knew that she was going back to London by the 11.00 a.m. express. Lady Ambermere was quite aware of it, and drove in with Pug and Miss Lyall, meaning to give her a lift to the station, leaving Mrs Quantock, if she wanted to see her guest off, to follow with the Princess’s luggage in the fly which, no doubt, had been ordered. But Daisy had no intention of permitting this sort of thing, and drove calmly away with her dear friend in Georgie’s motor, leaving the baffled Lady Ambermere to follow or not as she liked. She did like, though not much, and found herself on the platform among a perfect crowd of Riseholmites who had strolled down to the station on this lovely morning to see if parcels had come. Lady Ambermere took very little notice of them, but managed that Pug should give his paw to the Princess as she took her seat, and waved her hand to Mrs Quantock’s dear friend, as the train slid out of the station.

“The late lord had some Russian relations,” she said majestically. “How did you get to know her?”

“I met her at Potsdam” was on the tip of Mrs Quantock’s tongue, but she was afraid that Lady Ambermere might not understand, and ask her when she had been to Potsdam. It was grievous work making jokes for Lady Ambermere.

The train sped on to London, and the Princess opened the envelope which her hostess had discreetly put in her hand, and found that that was all right. Her hostess had also provided her with an admirable lunch, which her secretary took out of a Gladstone bag. When that was finished, she wanted her cigarettes, and as she looked for these, and even after she had found them, she continued to search for something else. There was the musical box there, and some curious pieces of elastic, and the violin was in its case, and there was a white mask. But she still continued to search….

About the same time as she gave up the search, Mrs Quantock wandered upstairs to the Princess’s room. A less highly vitalised nature than hers would have been in a stupor of content, but she was more in a frenzy of content than in a stupor. How fine that frenzy was may be judged from the fact that perhaps the smallest ingredient in it was her utter defeat of Lucia. She cared comparatively little for that glorious achievement, and she was not sure that when the Princess came back again, as she had arranged to do on her next holiday, she would not ask Lucia to come to a seance. Indeed she had little but pity for the vanquished, so great were the spoils. Never had Riseholme risen to such a pitch of enthusiasm, and with good cause had it done

so now, for of all the wonderful and exciting things that had ever happened there, these seances were the most delirious. And better even than the excitement of Riseholme was the cause of its excitement, for spiritualism and the truth of inexplicable psychic phenomena had flashed upon them all. Tableaux, romps, Yoga, the Moonlight Sonata, Shakespeare, Christian Science, Olga herself, Uric Acid, Elizabethan furniture, the engagement of Colonel Boucher and Mrs Weston, all these tremendous topics had paled like fire in the sunlight before the revelation that had now dawned. By practice and patience, by zealous concentration on crystals and palms, by the waiting for automatic script to develop, you attained to the highest mysteries, and could evoke Cardinal Newman, or Pocky….

There was the bed in which the Sybil had slept; there was the fresh vase of flowers, difficult to procure in November, but still obtainable, which she loved to have standing near her. There was the chest of drawers in which she had put her clothes, and Mrs Quantock pulled them open one by one, finding fresh emanations and vibrations everywhere. The lowest one stuck a little, and she had to use force to it….

The smile was struck from her face, as it flew open. Inside it were billows and billows of the finest possible muslin. Fold after fold of it she drew out, and with it there came a pair of false eyebrows. She recognised them at once as being Amadeo’s. The muslin belonged to Pocky as well.

She needed but a moment’s concentrated thought, and in swift succession rejected two courses of action that suggested themselves. The first was to use the muslin herself; it would make summer garments for years. The chief reason against that was that she was a little old for muslin. The second course was to send the whole paraphernalia back to her dear friend, with or without a comment. But that would be tantamount to a direct accusation of fraud. Never any more, if she did that, could she dispense her dear friend to Riseholme like an expensive drug. She would not so utterly burn her boats. There remained only one other judicious course of action, and she got to work.

Miss Mapp

Miss Mapp Works of E F Benson

Works of E F Benson How Fear Departed the Long Gallery

How Fear Departed the Long Gallery Dodo's Daughter: A Sequel to Dodo

Dodo's Daughter: A Sequel to Dodo The House of Defence v. 1

The House of Defence v. 1 Queen Lucia

Queen Lucia Night Terrors

Night Terrors Lucia Victrix

Lucia Victrix The Countess of Lowndes Square and Other Stories

The Countess of Lowndes Square and Other Stories The Second E. F. Benson Megapack

The Second E. F. Benson Megapack The Complete Mapp & Lucia

The Complete Mapp & Lucia The Blotting Book

The Blotting Book The E. F. Benson Megapack

The E. F. Benson Megapack Lucia Rising

Lucia Rising Ghost Stories

Ghost Stories Mrs. Ames

Mrs. Ames E. F. Benson

E. F. Benson