Miss Mapp

Miss Mapp Works of E F Benson

Works of E F Benson How Fear Departed the Long Gallery

How Fear Departed the Long Gallery Dodo's Daughter: A Sequel to Dodo

Dodo's Daughter: A Sequel to Dodo The House of Defence v. 1

The House of Defence v. 1 Queen Lucia

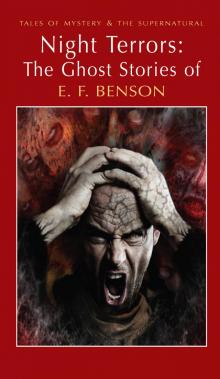

Queen Lucia Night Terrors

Night Terrors Lucia Victrix

Lucia Victrix The Countess of Lowndes Square and Other Stories

The Countess of Lowndes Square and Other Stories The Second E. F. Benson Megapack

The Second E. F. Benson Megapack The Complete Mapp & Lucia

The Complete Mapp & Lucia The Blotting Book

The Blotting Book The E. F. Benson Megapack

The E. F. Benson Megapack Lucia Rising

Lucia Rising Ghost Stories

Ghost Stories Mrs. Ames

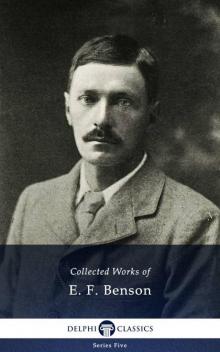

Mrs. Ames E. F. Benson

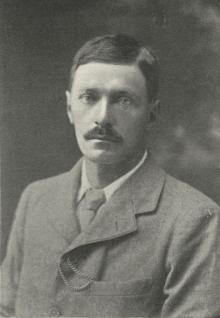

E. F. Benson